I first became acquainted with Jean-Gabriel Périot’s work in 2013, when his film The Devil was one of hundreds of submissions to the 2014 Wellington Underground Film Festival. I distinctly remember thinking: “this why I go through so many hours of submissions: to get to a gem like this.” I had no idea that Jean-Gabriel was already a well-known artist, and that his work has screened at prestigious festivals and institutions worldwide. At the time, The Devil was just another submission. This speaks to Jean-Gabriel’s humility and dedication to the field, that he is not taken in by the art world. For me, it was a perfect match, and I would go on to screen more of his films in future festivals.

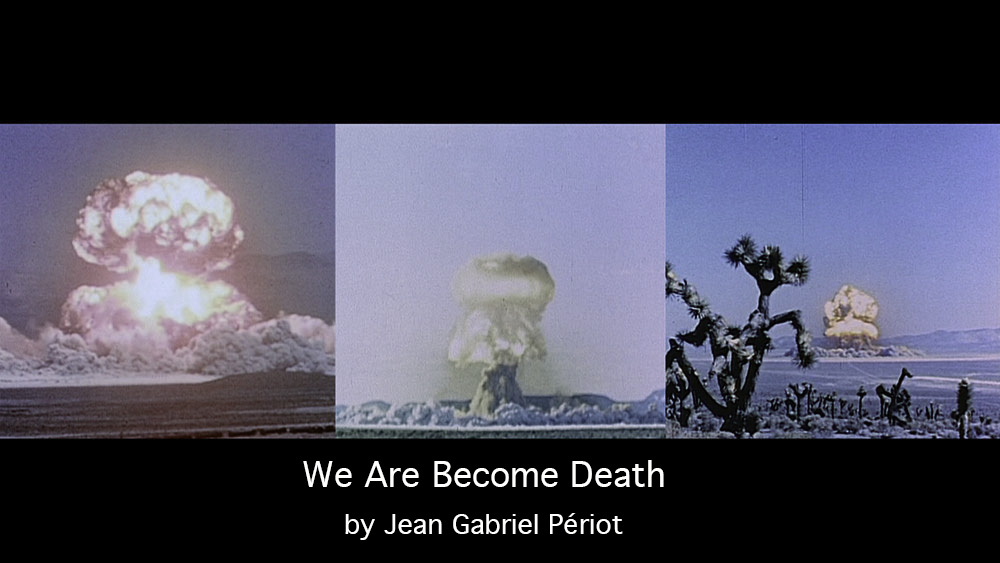

Jean-Gabriel’s work often touches on the history of violence – a sobering topic. But instead of leaving us in despair, his films remind us of the unbending resilience of the victims, and the survivors, of violence. Made with archival footage, juxtaposed with music, Jean-Gabriel Périot articulates – through sound and moving image – what is so difficult to articulate with words.

– Rosie Rowe

How did you get started as a filmmaker?

It’s quite simple. When I was a child, I was lucky to go regularly to the movies. My father used to bring me regularly to the cinema and my mother was living in front of a small cinema where I could go alone. Later, when I was teenager, I could take the bus alone from my father and go to the cinema. I really enjoyed seeing so many films and when it was time to choose what to do as work, I decided that to make films would be a wonderful job.

When I ended my studies – nothing interesting there – I started to work as an editor, mostly on documentaries. I was satisfied with my work, as I was editor on interesting projects, and I was well paid! But I was missing something, and finally I decided it was time to start my own work. For many years, I did my job as editor and made my own films.

Is there anyone you especially appreciate and look to for inspiration?

Not especially. Except Vertov. I’m not sure about all his films, but I’m still amazed by his ideas about cinema, particularly about filming and editing as a language that should be separate from other narrative arts. To make cinematographic films is the only way to make political films efficient.

One aspect of your films that I really appreciate is your ability to present pretty dark, cynical aspects of humanity. But instead of walking away with dread, there is a feeling of hope in the resilience of the victims of violence. Does this quality represent a core, personal philosophy?

It’s complicated for me to express what could be my philosophical or even personal stances or point-of-view. I do films because it helps me to make my thoughts precise, or at least to make them less blurry. It’s a way to think.

But you’re right. Even if many of my films deal with disasters, violence – all the dark sides of humanity – I don’t want to make desperate films. Some parts of the past were devastating, parts of the world today are suffering; even in safer countries, people could experience a painful life. Myself…I’m quite secure, and I never experience such miseries. For me, it would be unethical to make films from the “point of view” of the people who have appeared in my films. They could only be made from my point-of-view. It’s not that my point-,of-view is better or whatever, it’s that I can’t pretend to speak for others. Or pretend I could translate or transcribe their pain in a film.

My films question the past and the present from the point-of-view of someone who is lucky. For me, it’s really important to state that. Because one could only fight to preserve his own world and to help others if he’s aware that there is always a worse situation than his. So many just complain all day long; it’s really indecent…. We should appreciate our everyday life, and people around us, in respect for all the ones who suffered and still suffer and to be able to fight for them. In a way, there is always a principle of hope, even in my most despairing films.

A friend of mine once told me that they write a poem with the last line first, then go back to the start of the poem and ‘sprint’ to the end. What’s your process with your filmmaking? Do you find an image or sound first and work around it? Or do you formulate an idea first, then search for images to convey it?

It really depends on the film. For some, I first have an idea and then I start research to find the archival footage or photographs that I could use, like for Nijuman no borei, Undo or A German Youth. For sure, the images I find change the project, but the beginning of these films is always a question. For others, the idea could come from images I see. I regularly watch films and look at pictures, but sometimes, some strike me or affect me more than others. It could be only one or a group of them. They usually stop me because I don’t understand them and/or I learn something from them. It was like that for Even If She Had Been A Criminal… and for The Devil.

Looking through your collection of films, there’s one that stands out for me: Lovers. It’s a collection of pornography that runs roughly twenty minutes and follows the arc of sex – more importantly, gay sex. Do you think a film like Lovers is only ‘screenable’ in queer spaces? Or have you experienced wider acceptance of the film in the general avant-garde, experimental or underground film spaces?

I’m quite uncomfortable with this film and with some others that are dealing with LGBT, or even more personal, topics or some that are more humorous. When I did Lovers, I was looking for something. I worked on the film and was quite satisfied with the result, but to screen such a film was not so easy. On one hand, there is a real problem of explicit images. Almost everywhere, such a film can’t be screened with an audience with people under 18. But on the other hand… for me this film is too private, too personal. So after I did it, I didn’t really push too much to organize screenings or to send it in festivals. The few screenings of the film mostly happened in queer film festivals. There were also few screening in “straight” festivals, like during retrospectives of my works, and that was ok. But the film was never screened – or perhaps once or twice, I don’t remember – in experimental film festivals. Usually, my works – and not this one – are rarely shown in such festivals. Probably they are too narrative or documentary for programmers. That is quite fair, as I could define only a few of my films as “experimental,” and I hate when festivals screen them in side programs as experimental or avant-garde programs. I do films, and nothing is more pointless than separating films into genres.

In my day job, I preserve archival audiovisual material. I know you work with archival footage. Is there anything that archives and other memory institutions can do to help artists like yourself? Is there content you aren’t able to find?

There are probably two ways archival institutions could help filmmakers’ or artists’ work. The first one has more to deal with relationships. Filmmakers sometimes know exactly what we are looking for. But sometimes, we don’t really know. Myself, I sometimes want to jump into an archive and see what could be there. I wish to go through the database of the institution, to read the titles of the films or news on the tapes and prints, to lose time by randomly watch footage. That is always impossible. We always need to provide a precise list of what we are looking for. But it’s complicated, particularly when our topic is wide. We could find archives of certain materials (like from books), but we could also find interesting material by chance. I also believe that it’s important to work from both perspectives. So it could be useful if institutions could change some of their own practices.

The second way institutions could help us is simply to offer filmmaker and artists the opportunity to make projects with their archives. Like “Hey, we have ten hours of that kind of archive, there is no problem of rights, and we digitized them. So just help yourself and make a film with those if you want to.” It’s really exceptional when institutions like cinematheques offer such a free way of working. Most of the time, when they try to do so, they do it like they would for a commissioned film, so with preconceived ideas about the film to be made. Or they offer really boring archives. Then they think or believe that a filmmaker will be able to create something with that, that will give those uninteresting footage some ”value.” In a way, almost all of the institutions that have archives are quite afraid to be dispossessed. Some trust is always missing.